PwC released the results of new analysis and research on March 8, the Women in Work Index and the Global Empowerment Index, which provide a detailed look at gender-focused matters affecting the global workplace.

The Women in Work Index (WiW) shows that progress towards gender equality remains too slow. The analysis demonstrates that at the rate the gender pay gap is closing, it will take more than 50 years to reach gender pay parity.

It also shows a slight fall in the unemployment rate for women, from 6.7 per cent to 6.4 per cent, in 2021. However, similar improvements were also evident in male participation and employment rates, suggesting that employment levels are a symptom of macro-economic factors and the general labor market recovery rather than an advancement towards gender equality.

The Global Empowerment Index, meanwhile, found that there is a significant gender empowerment gap, with men being more empowered in the workplace than women. The Index is based on an analysis of gender-focused perspectives from almost 22,000 working women around the world and measures 12 factors of empowerment across four dimensions of empowerment: autonomy; impact; meaning and belonging; and confidence and competence.

The four most important workplace empowerment factors for women, which are also the top four considerations for women deciding to make career changes, are: Fair compensation (72 per cent), Job fulfilment (69 per cent), A workplace where they can truly be themselves (67 per cent), and Having a team that cares about their well-being (61 per cent).

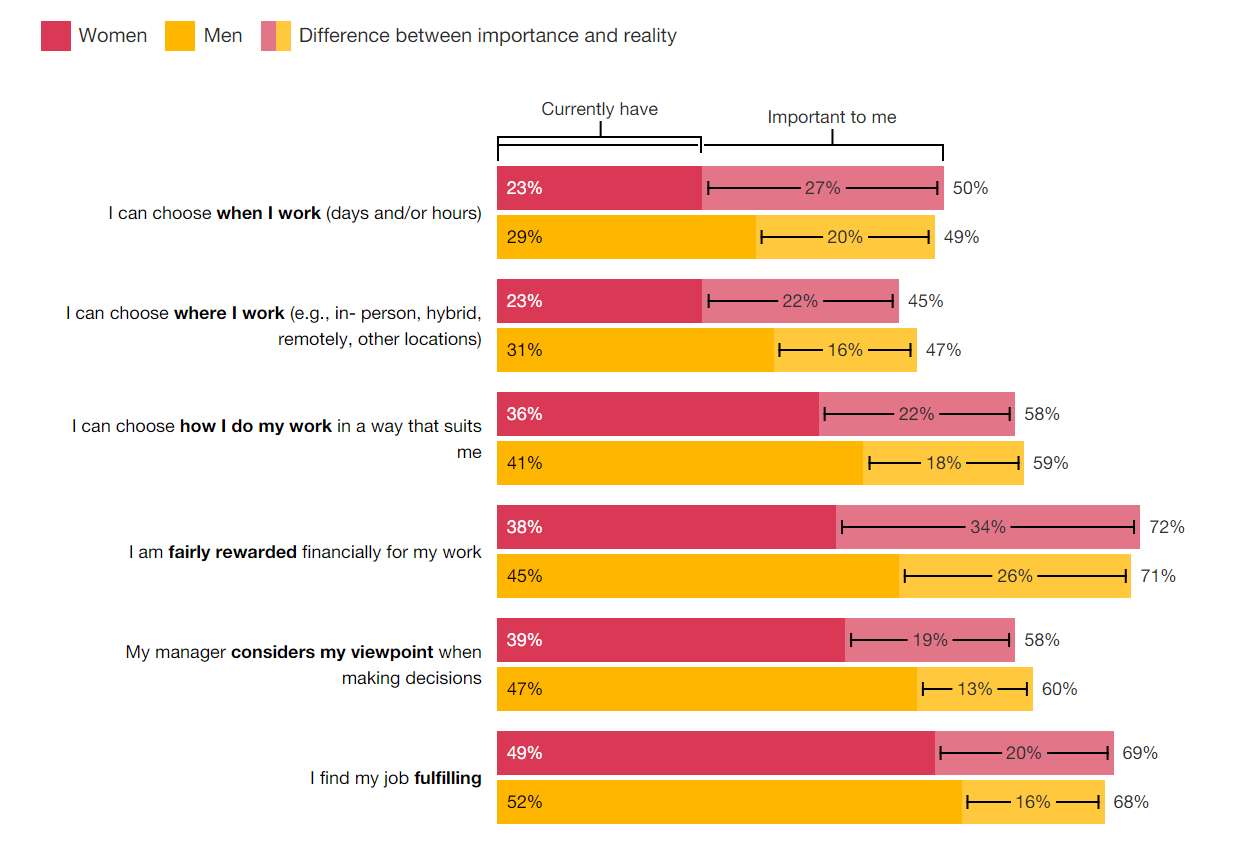

The research found that men and women are broadly similar in how important each empowerment factor is to them. However, men were more likely than women to say that they actually benefited from these factors at work.

The biggest gaps for women are in fair reward (34-point gap between importance and reality), choosing when (27 points), where (22 points) and how (22 points) they work, job fulfilment (20 points), and having a manager consider their viewpoint when making decisions (19 points).

The women in the survey with the highest empowerment scores were more likely to ask for a raise (55 per cent) and more likely to ask for a promotion (52 per cent). This compares with scores of 31 per cent (a 24-point gap) and 26 per cent (26 points), respectively, for women in the survey overall.

According to the Global Empowerment Index, the most empowered women workers are in the Technology, Media, and Telecommunications sector, driven specifically by the Technology industry, for which women are slightly more empowered than men. Women working in the Financial Services and Energy, Utilities, and Resources sectors are the second and third-most empowered, but men are significantly more empowered than women in Financial Services.

Ms. Angela Yang, Inclusion & Diversity Leader at PwC Vietnam, said that despite some gains in the workplace, the need to bridge inequality between women and men at work is still urgent in Vietnam, where gender-based discrimination is resulting in a gender pay gap, low female-to-male ratios in top management, and women’s dissatisfaction about career prospects.

The PwC research shows that diverse companies, where more than 30 per cent of leaders are women, are, on average, 15 per cent more profitable than those that aren’t diverse, and businesses that score highly on sustainability tend to outperform those that don’t. CEOs and employers have a responsibility to establish a workplace that promotes gender equality, where women feel equally empowered and are compensated fairly.

Additionally, they should strive to create an environment that gives women a sense of autonomy, purpose, and belonging. This approach will not only help foster trust within the organization but also encourage women’s professional development.

The WIW also shows a startling reality: the motherhood penalty is now the most significant driver of the gender pay gap. The unfair share of childcare perpetuates the “motherhood penalty” - the loss in lifetime earnings experienced by women raising children, brought about by underemployment and slower career progression upon returning to work after having a child.

This is observed directly as a 60 per cent drop in earnings for mothers compared to fathers in the ten years after the birth of the first child (as measured across six OECD countries), and more broadly in women’s lower balances of pension and retirement savings at the end of their working lives.

Ms. Yang also noted that harmful gender norms and expectations of women and men perpetuate the motherhood penalty, which is now the most significant driver of the gender pay gap. “Policy solutions are needed to address the underlying causes of inequality, such as affordable childcare, redistributing unpaid childcare more equally between women and men, and redesigning parental leave policies to support a dual earner-dual career model,” she added.

Google translate

Google translate